Periodization has long been a subject of intense debate among coaches and professional athletes. But since the transition into the information age, it is being discussed by so many everyday fitness enthusiasts that it’s become one of the hottest topics ever in the sports industry. Hundreds of articles, books and studies are being published in an attempt to give a better understanding of how it all works, but this bombardment of information can often times prove to be confusing, or even conflicting for many readers. Let’s put some order into this chaos.

First of all, we should define what exactly we’re talking about. According to Hungarian-Canadian endocrinologist Hans Salye’s General Adaptation Syndrome theory (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2038162/pdf/brmedj03603-0003.pdf), our body can experience three conditions when confronted with a new stimulus. These are called the alarm, the resistance and the exhaustion. During the initial alarm phase, the system is shocked and the stimulus is perceived as stressful. Shortly after, it shifts to the resistance phase, in which it functions at a higher metabolic level, thus creating adaptations in order to withstand the imposed stressor. This is the phase in which growth takes place. Finally, if the body is stimulated for too long, its energy reserves are depleted, which results in catabolism and a suppressed immune system. So, plainly put, periodization is the systematic, structured planning of training, the ultimate goal of which is to keep the athlete in the resistance phase for as long as possible while avoiding overtraining/overreaching.

The three basic models of periodization -there are plenty more but not all can be discussed in a single article- are the Linear/Western model, the Block model and the Undulating/Non-linear model. We will contemplate the pros and cons of each one by investigating them from a single perspective; the fighter’s perspective.

Linear/Western Periodization

This is the most famous periodization model in the history of mankind. Literally everyone has used it at some point, and it’s the one which the casual gym rat instinctively performs. It was devised in the 1950s by Russian scientist Leo Matveyev, and is based on slow, progressive weight overload. It is essentially an escalator that aims to guide the athlete to a single peaking point in the season.

It consists of macrocycles, mesocycles and microcycles. The macrocycle is, quite simply, the whole annual plan. The mesocycle represents a specific period within the macrocycle, usually lasting anywhere between three to six weeks, depending on individual requirements. The microcycle is the smallest part of the program, typically a week’s worth of training, and is planned based on where it is located in the overall macrocycle. The programming begins with a hypertrophy phase, followed by a strength phase, continues with a power phase and ends with the peaking phase.

Linear Model Parameters – Hypertrophy

In a classic hypertrophy mesocycle, the parameters are usually as follows:

Loads: 60-70% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 3-5.

Reps per set: 8-20.

Rest between sets: 60-90″. Needless to say, in the case of super sets the rest duration should be minimal to none. If you stop for more time than it takes to switch between exercises, you are not doing a super set.

Frequency: Train each muscle group directly or indirectly two to three times a week.

Example:

Week 1: 5 sets | 12 reps | 60% load | 60-90″ rest

Week 2: 4 sets | 10 reps | 63% load | 60-90″ rest

Week 3: 3 sets | 10 reps | 66% load | 60-90″ rest

Week 4: 3 sets | 8 reps | 70% load | 60″ rest

Linear Model Parameters – Strength

We’re moving into the strength phase. Here’s an example of what it looks like:

Loads: 71-85% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 3-5.

Reps per set: 3-6.

Rest between sets: 3-4′. Since at this point we’re much more interested in giving the muscles enough time to reload ATP rather than causing a metabolic response, if you don’t feel at least 90% ready to begin the next set, by all means use even more rest than what’s prescribed. Your nervous system and fuel reserves must be as fresh as possible.

Frequency: Since we’re looking for neurological adaptation, you should train each muscle group three or even four times a week, depending on the circumstances.

Example:

Week 1: 5 sets | 6 reps | 73% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 2: 4 sets | 5 reps | 77% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 3: 4 sets | 4 reps | 81% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 4: 3 sets | 4 reps | 85% load | 3-4′ rest

Linear Model Parameters – Power

Now it’s time for the power mesocycle. Let’s take a look:

Loads: 86-92% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 3-4.

Reps per set: 3-4.

Rest between sets: 3-4′. Again, don’t be afraid to use plenty of rest if needed.

Frequency: Hit each muscle group three to four times a week.

Example:

Week 1: 4 sets | 4 reps | 86% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 2: 4 sets | 4 reps | 88% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 3: 3 sets | 3 reps | 90% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 4: 3 sets | 3 reps | 92% load | 3-4′ rest

Linear Model Parameters – Peaking

The last part of the macrocycle is the peaking phase:

Loads: 93-100% of 1RM. The athlete could also attempt new PRs at this stage, but if that’s the case a deload week should be considered right before the PR week.

Sets per exercise: 2-3.

Reps per set: 1-3.

Rest between sets: 3-5′. As per the strength and power phase, take a lot of rest in order to ensure that each set is performed in the most efficient and safe way.

Frequency: Hit each muscle group three to four times a week.

Example:

Week 1: 3 sets | 3 reps | 93% load | 3-5′ rest

Week 2: 3 sets | 3 reps | 96% load | 3-5′ rest

Week 3: 2 sets | 2 reps | 98% load | 4-5′ rest

Week 4: 2 sets | 1 reps | 99-100% load | 4-5′ rest

The Verdict

As you can see, the linear periodization model aims to slowly increase the intensity and simultaneously lower the volume. Evidently, it is best for athletes who only need to peak once a year, like runners who prepare for an annual marathon or lifters who only have one specific event to prepare for. It is also great for beginners in any discipline, since it constitutes a great way to build a robust foundation for the future, while offering a gentle learning curve. On the other hand, It is not really advised for athletes with longer seasons or professional fighters who get into the ring/cage more than once a year, therefore are best off with a model that helps them peak frequently. We will talk about this in a minute. Another side-effect can be that towards the end of the macrocycle, the athlete is spending a lot of time under heavy loads and may experience central nervous system (CNS) fatigue. Lastly, the linear model is highly fragile to changes. If a few training sessions or microcycles (weeks) are skipped because of injury or life conditions, how do we make up for it? Do we completely ignore them? Do we perform them when the athlete is back and skip another part of the program? Or do we merge some of what was lost with some of what’s coming? Just a few questions to ponder over.

Block Periodization

After the Linear periodization model was conceived, it tended to serve mostly athletes who solely competed at the Olympic games, meaning that they had four years to prepare for a single event. As time passed and sports evolved, the needs of professional athletes changed greatly. A program that would focus on a smaller set of skills and help them peak multiple times per season was now needed. This is exactly the problem that Russian researcher Yuri Verkhoshansky came to solve by proposing the Block Periodization model.

This model has gained much popularity in recent years, and is typically based on the division of the training period into three (sometimes more) distinct blocks, or mesocycles if you prefer, each lasting anywhere from two to four weeks. These are the accumulation block, the transmutation block and the realization block. Let’s take a look at a generic blueprint of the block periodization model.

Block Model Parameters – Accumulation

The first phase is all about accumulating basic technical and motor skills. It contains mostly general and general-specific lifts.

Loads: 50-75% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 3-5.

Reps per set: 8-20.

Rest between sets: 30-120″.

Frequency: Ideally, each muscle group must be trained two to three times per week.

Example:

Week 1: 4 sets | 15 reps | 55% load | 30-60″ rest

Week 2: 4 sets | 12 reps | 60% load | 60-90″ rest

Week 3: 3 sets | 10 reps | 65% load | 60-90″ rest

Week 4: 3 sets | 8 reps | 72% load | 60-90″ rest

Block Model Parameters – Transmutation

This block is about transmuting the acquired skills into practical abilities and mostly oriented towards sport-specific exercises.

Loads: 76-90% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 3-4.

Reps per set: 3-6.

Rest between sets: 2-4′.

Frequency: Three to four times of direct or indirect stimulation per muscle group, per week.

Example:

Week 1: 4 sets | 6 reps | 80% load | 2-3′ rest

Week 2: 4 sets | 5 reps | 85% load | 3-4′ rest

Week 3: 3 sets | 4 reps | 90% load | 3-4′ rest

Block Model Parameters – Realization

The last part is about realizing the abilities obtained and achieving the desired outcome. Most general or general-specific lifts are flushed out at this point, and performance is expected to be up to the standards of competition.

Loads: >91% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 2-3.

Reps per set: 1-3.

Rest between sets: 3-5′.

Frequency: Each muscle group should be trained three to four times per week at this stage too.

Example:

Week 1: 3 sets | 2 reps | 95% load | 3-5′ rest

Week 2: 2 sets | 1 rep | 99-100% load | 4-5′ rest

The Verdict

By now it is clear that this model seeks to consecutively develop particular capacities, thus giving the practitioner the ability to peak multiple times per season, as is demanded by a lot of modern sports. Powerlifters can benefit from it too, since the physical traits they need to develop are not many. It is often prescribed for combat athletes who fight multiple times a year, but it’s not the most suitable approach for self-defenders. More on this soon. On the other hand, in my opinion it is definitely not recommended for beginners, who are primarily in need of establishing a wide and steady base via a more uniform experience, as mentioned earlier. It is worth bringing up that a research from 2014 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24476775/) compared the performance of two groups of lifters that used either the linear or the block system, and favored the latter overall. But it is important to note that the study only lasted 15 weeks, whereas the linear periodization model requires much more time for its results to manifest. Therefore, this is not enough proof to simply choose one methodology over the other as purely superior, at least in my eyes.

Undulating/Non-linear Periodization

This final model is established on the principle of constantly changing the training variables in terms of volume, intensity, density, exercises, and so on. Representing the other end of the spectrum if compared to the Linear model, the idea here is to expose the body to different types of stimuli more frequently. As a note, variability does not equal arbitrary selection of exercises. The most usual applications of the Undulating model are the weekly and daily variations, in which the training parameters are changed every week or every training session, respectively. Like the Block periodization, the Undulating style has been widely used by professionals and amateurs alike, mostly in the last 20 years. This is what a weekly Undulating model might look like.

Undulating Model Parameters

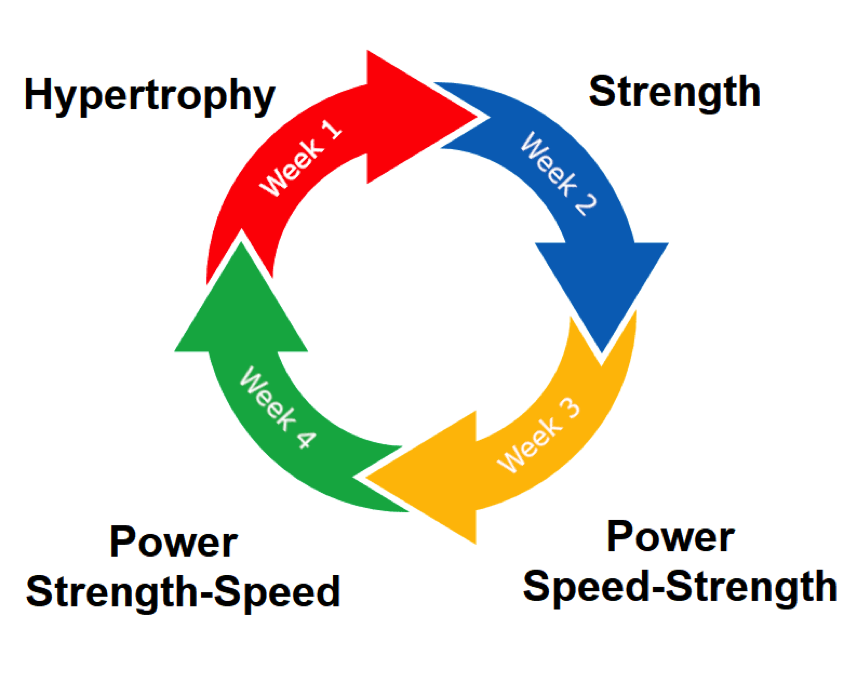

In this instance, the training schedule has been divided into four parts/weeks, sequentially dedicated to hypertrophy, strength, speed-strength and strength speed. When a full circle is completed, the program is restarted. We can easily witness the fluctuations in loads and training stimuli, which is the main principle of the Undulating periodization model.

Week 1 | Hypertrophy

Loads: 65-80% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 3-4.

Reps per set: 6-12.

Rest between sets: 30-120″.

Frequency: Hit each muscle group two to three times during the week.

Week 2 | Strength

Loads: 80-90% of 1RM.

Sets per exercise: 4-6.

Reps per set: 3-6.

Rest between sets: 2-4′.

Frequency: Hit each muscle group three to four times during the week.

Week 3 | Speed-Strength

Loads: 10-30% of 1RM on ballistic exercises (i.e. jumping back squat) and 60-70% on Olympic lifts (i.e. hang power clean).

Sets per exercise: 3-6.

Reps per set: 2-10, largely dependant on the exercise.

Rest between sets: 2-4′.

Frequency: Again, train each muscle group three to four times for this week.

Week 4 | Strength-Speed

Loads: 50-70% of 1RM on the standard lifts and 70-80% on Olympic lifts.

Sets per exercise: 3-6.

Reps per set: 2-6.

Rest between sets: 2-4′.

Frequency: As in the previous two weeks, train each muscle group three to four times.

The Verdict

The Undulating periodization model is excellent for maintaining a high level of competency in many qualities for long periods of time, without allowing any of them to detrain since all are being practiced often. With this in mind, if an athlete skips a session because, you know, life happens, it’s not that big of a deal. It is also the model of choice for any athlete whose season lasts very long, or for competitive fighters who do not yet know the exact date of their fight in order to program their peak. It should also be the preferred method of training for self-defense practitioners, considering that they are preparing for the unknown, therefore they can never know if and when they might need their skills. Plateaus, the lifter’s worst nightmare, rarely occur due to the continuous alterations of stimuli. Last but not least, it is definitely a more fun way to train since constant variation keeps monotony at bay. As far as disadvantages go, you will have to choose your accessory work wisely, because the minimalist selection of exercises might cultivate muscular imbalances over time.

Final Thoughts

Before we conclude, I would like to highlight a potential pitfall of the percentage loading model that was used in all of the above program illustrations. Strength isn’t always as fixed and linear as we would like to assume when writing programs. All prescribed loads are calculated hypothetically, based on the 1RM, but factors like recovery, time off or the psychological state of the athlete are never taken into consideration in this equation. What if you’re coming back from a hiatus? Your 1RM is no longer the same, and you currently have no idea what it is. Also, what about these bad days where your mood is awful and submaximal loads feel like you’re lifting the whole world? If for some reason your CNS is trashed, you should be mindful of the weight you use. Love the hard work, but always listen to your body and adjust. With that said, I hope some light has been shed on the infamous periodization conundrum. All the theory in the world is no good if we do not apply though, so now that you understand the founding principles put your tools to the test and find out what works best for you in order to reap the maximum benefit. Good luck!

Alex Chrysovergis

Comments are closed.